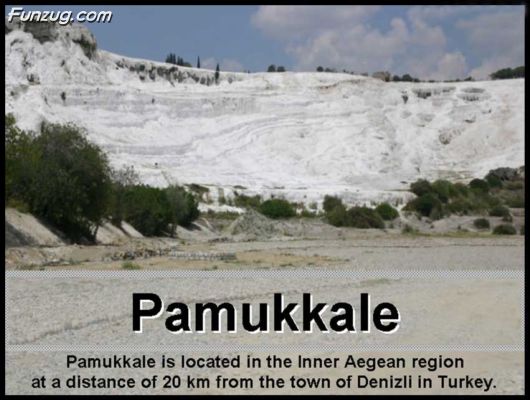

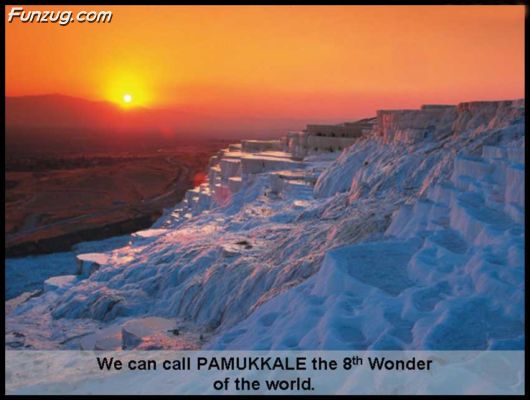

Pamukkale is located in the Inner Aegean region at a distance of 20 km from the town of Denizli in Turkey.

Pamukkale (Hierapolis) translates to Cotton Castle.

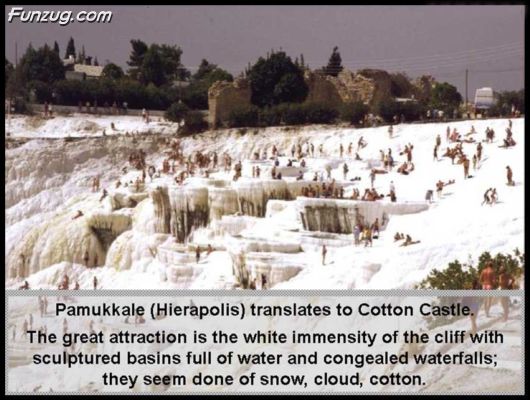

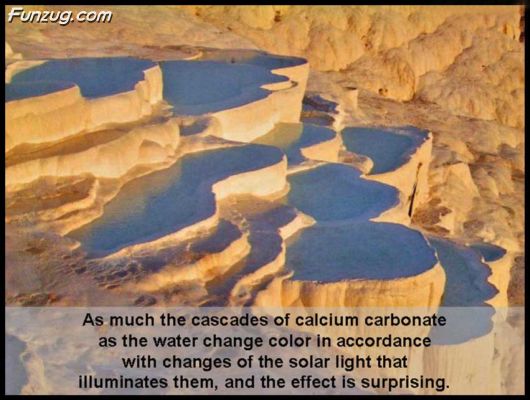

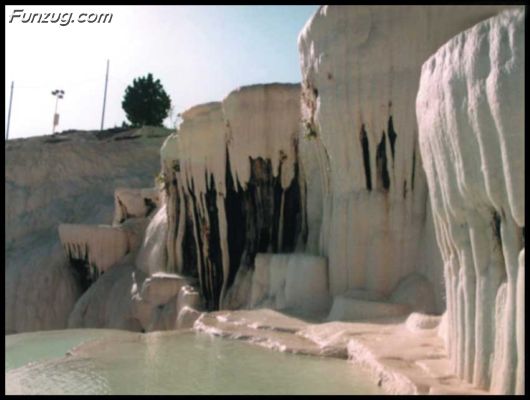

The great attraction is the white immensity of the cliff with sculptured basins full of water and congealed waterfalls; they seem done of snow, cloud, cotton.

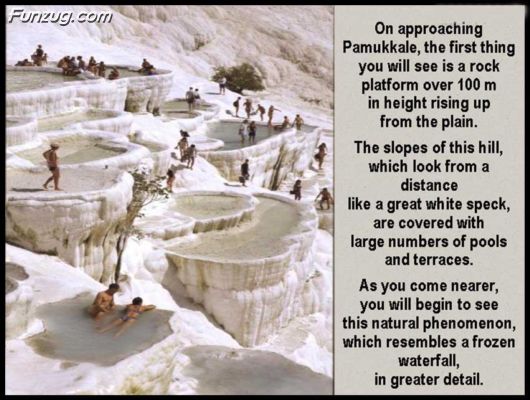

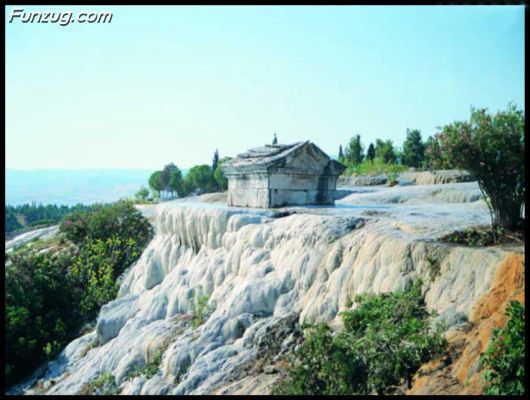

On approaching Pamukkale, the first thing you will see is a rock platform over 100 m in height rising up from the plain.

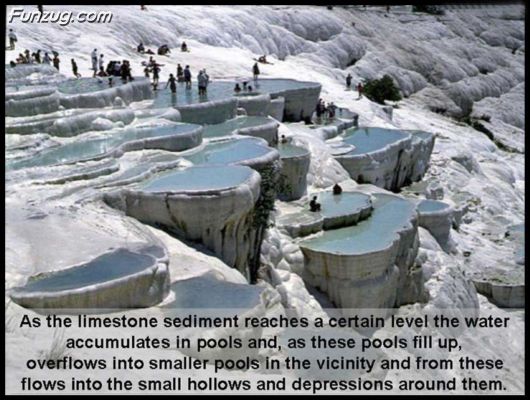

The slopes of this hill, which look from a distance like a great white speck, are covered with large numbers of pools and terraces.

As you come nearer, you will begin to see this natural phenomenon, which resembles a frozen waterfall, in greater detail.

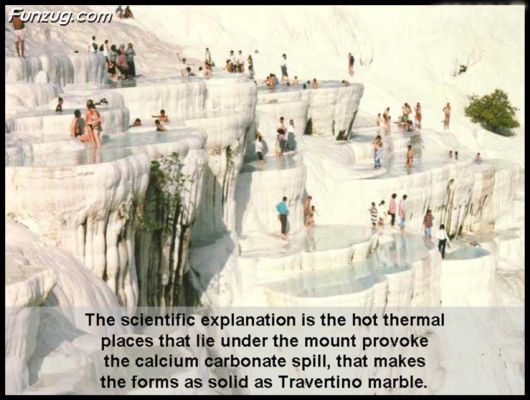

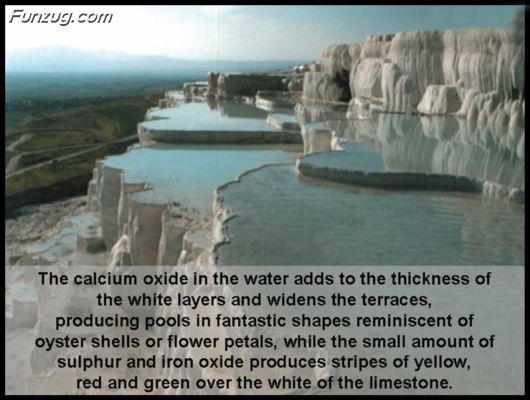

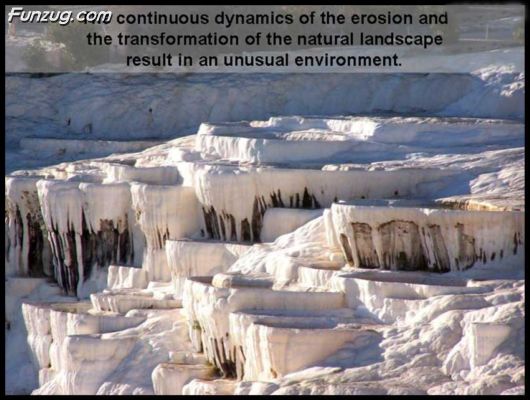

The scientific explanation is the hot thermal places that lie under the mount provoke the calcium carbonate spill, that makes the forms as solid as Travertino marble.

The temperature of the water forming the travertines, which issues from the hot springs on the hills above, falls to around 33°C lower down.

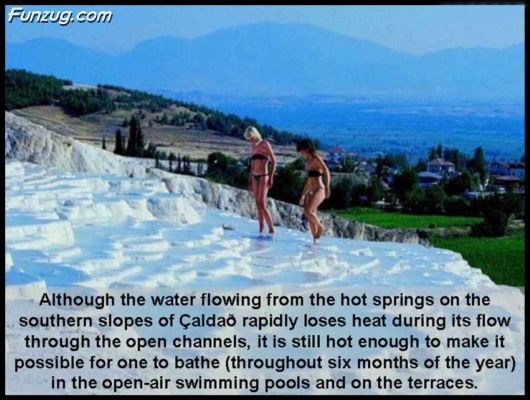

Although the water flowing from the hot springs on the southern slopes of Çaldað rapidly loses heat during its flow through the open channels, it is still hot enough to make it possible for one to bathe (throughout six months of the year) in the open-air swimming pools and on the terraces.

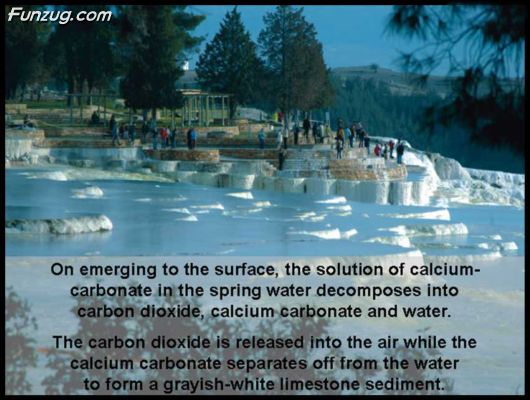

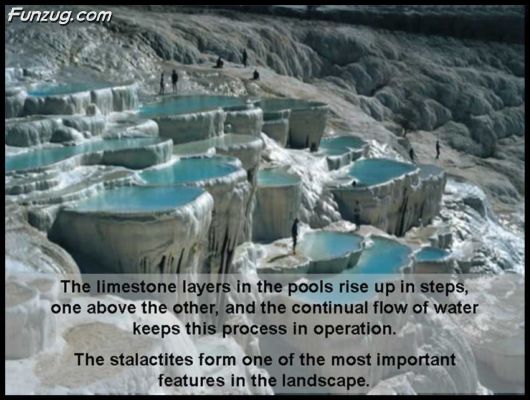

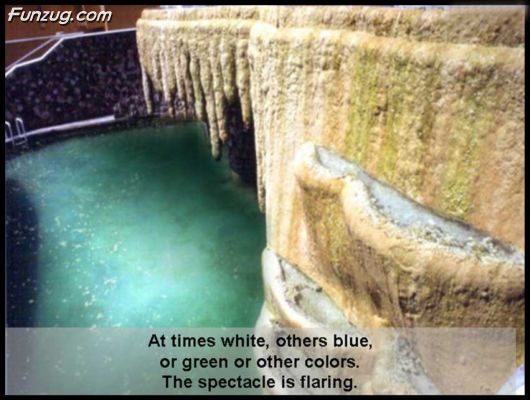

On emerging to the surface, the solution of calcium-carbonate in the spring water decomposes into carbon dioxide, calcium carbonate and water.

The carbon dioxide is released into the air while the calcium carbonate separates off from the water to form a grayish-white limestone sediment.

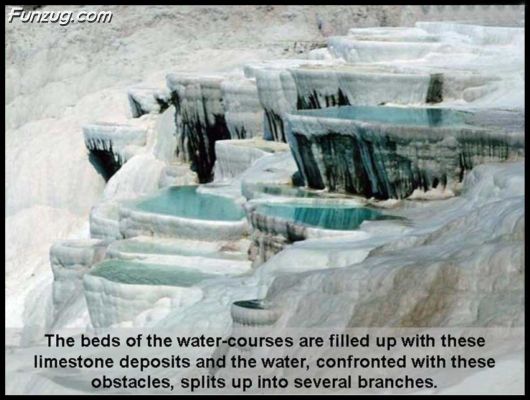

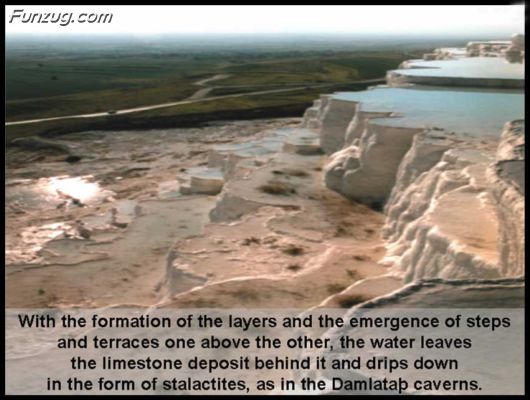

The beds of the water-courses are filled up with these limestone deposits and the water, confronted with these obstacles, splits up into several branches.

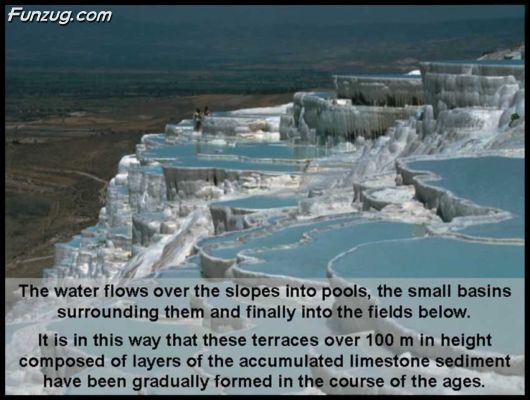

The water flows over the slopes into pools, the small basins surrounding them and finally into the fields below.

It is in this way that these terraces over 100 m in height composed of layers of the accumulated limestone sediment have been gradually formed in the course of the ages.

As the limestone sediment reaches a certain level the water accumulates in pools and, as these pools fill up, overflows into smaller pools in the vicinity and from these flows into the small hollows and depressions around them.